PICTORIAL STORY

January 22, 2023

THE RESURRECTION OF RUBINO

Photography by Aaron Rubino

Story by Gary Nolan

Introduction by Karen Ghostlaw Pomarico

As photographers we often wonder what will happen to our archives after we are gone. Will our photographic journey continue? Or do our images die with us like our last thoughts when we take our final breath? For some, photography was their profession, besides a passion, taking thousands of images that one day will become the responsibility of someone else. The burden to archive and care for another photographer's negatives, while respecting their relationship to their camera and the connections they made through the lens. A daunting task for anyone.

We have the great pleasure of highlighting a photographer's work that has been tucked away, and hiding in the shadows, being cared for by a friend. Recently they were offered to Gary Nolan. They trusted Gary to keep them safe, and shed some light on Aaron Rubino’s photography and respect the memory of his friend.

Gary shares how he acquired this archive of Aaron Rubino, and what his thoughts have been while witnessing the visual stories that have been left now in his care. Gary raises many interesting questions, and has invested much time and thought addressing issues that as photographers we all will face, when we no longer see through the lens.

-min.jpg)

After visiting my elderly friend Tom in San Francisco earlier this year, I returned home in possession of a large set of negatives (1700+) taken by Aaron Rubino, his deceased friend who had given him the film years earlier. The cache of negatives had recently escaped serious water damage from a pipe break and Tom, now considered a quadriplegic in the state of California and battling cancer, was starting to wonder what would happen to everything after he was gone. Since I had been involved in photography and imaging for most of my career, he insisted I take them.

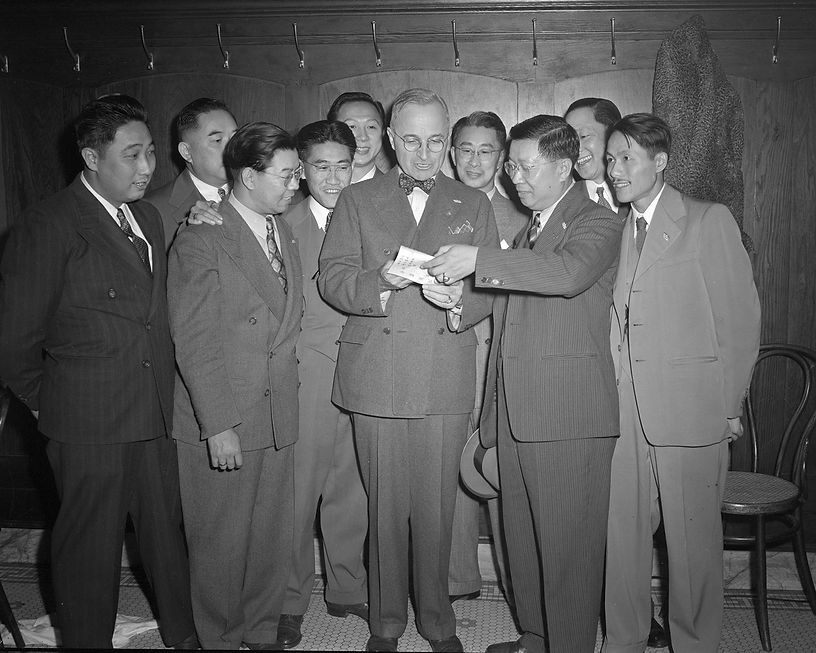

Rubino had been a photojournalist and had a freelance business in the city as well. Looking over the sparse notations scribbled on the negative sleeves, most of the photo shoots and sessions were from the period 1944-1949, with the majority dated 1944 or 1945. Subject matter was all over the map - group and PR shots, weddings, sports, entertainers, politicians, street scenes, some WWII related stuff, fashion, even a few ‘boudoir’ type images. My friend was not certain why he’d ended up with all the film, saying Rubino had no interest in any of it near the end of his life and just offered them up to Tom without much comment or reason.

After looking through many of the negatives and scanning a few on my return to Ohio, I felt some of the images possessed an oddly interesting aesthetic. They also presented a weird tableau of the times and possibly had some historical interest. What I had not anticipated was feeling an odd affinity to the images, the photographer, and even the people in the photos. Even more, it started me questioning the nature of photos again and asking why these images, perhaps given their age, invoked some peculiar, different, and somewhat random thoughts.

A PARALLEL UNIVERSE

At first glance, the images somehow look a bit surreal and, at times, almost cartoonish. A few other people I showed them to had the same reaction - something like seeing a sci-fi film about a parallel world, one similar to ours on the surface yet ‘different’ in some fundamental, non-obvious way. Why? Is it simply because of the age of the images? Do photos have an expiration date or a half-life? Do they suddenly pass from being contemporary and recognizable before fading into some frozen diorama of antique irrelevance? People are still people and yet the props, the clothing, the state of technology all conspire to create some parallel world - something vaguely familiar but somehow quite distant and foreign from what we know. It is a curious phenomenon.

An argument can be made, as Marshall McLuhan did in 1964, that the ‘medium is the message’. The reason these images influence us this way is dictated by the photography - the lack of color, the use of a hard on-camera flash, the peculiarities of the camera or lens, the technical limitations of the film, on and on. Since the ‘medium’ was less accessible to many back then, everything that survives and persists in our collective culture has a similar look and feel, caused solely by the distinctive images produced by the press cameras and flashbulbs of the day.

Still, there’s more than just the medium embedded in those messages. Cultural norms are everywhere in the photos - dress fashions, hair styles, furnishings, decor, architecture. Signs of technology also creep in at every turn - automobiles, kitchen appliances, microphones, airplanes, sports equipment, cash registers, telephones, etc. Our visual landscape has shifted so radically that those things appear only vaguely familiar and seem more like museum oddities. Even the sometimes stilted posing and exaggerated expressions create a sense of simulated reality, adding to the already alien feeling running through the images. Other than a few subjects in the photos staring back and breaking the fifth wall, it is difficult to identify with any of it.

I suppose if cell phone photos were as ubiquitous then as now, we would be having a completely different discussion about this, but unfortunately I think it is reasonable to say that nearly all images will suffer this same fate. As a corollary, I also think it’s inevitable that we may all look like cartoon characters in images viewed by future generations given the passage of enough time. About 75 years have passed since most of Rubino’s photos were captured and that number could be a defining line - about 2 generations - where technology and social norms shift so much that anyone viewing in the future may be more distracted by the differences and no longer see the similarities. If we add in the exponential growth of technology (Moore’s Law) and the accelerated rate of change caused by the web and social media, the defining line where the familiar passes some event horizon and out of existence could be compressed to a much shorter span of years.

DEAD PEOPLE WALKING

The other, perhaps obvious, observation is that most of the people in these images are now dead. All the muscular boxers, crowds on the street, women trying to look attractive, sailors, politicians, wedding-goers, businessmen, athletic teams - probably all gone. The more I scanned, the more I started getting concerned about that fact. Who were these people? How had their lives turned out? Did they have families? Had they been happy? Venturing down that philosophical road was, I realized, probably a one way journey, yet I felt a lot of expectant eyes staring back at me while I retouched and adjusted digital images. All the film had sat, somewhere, dormant for over 70 years since being viewed or printed - perhaps some of them had never been seen. Now they were back on the screen, being viewed by myself and a few others. It was as if I had poured water over these two dimensional pieces of celluloid and witnessed the reanimation of all these people - watching the smiles and the bright eyes coming back to life, realizing that those people are not a day older than they were in 1944 or 1945.

In earlier times, Native Americans were wary about having their photographs taken, fearing the process stole part or all of their souls. Perhaps it sounds strange, but I considered that notion too for a time while working with these images, as if some unknown part of these people had now resurfaced, returning some of the essence of what was ‘taken’ from them in that original moment the photo was shot. They are physically gone, but this dancing chimera remains on screen, so what exactly is it that’s left? Do I now owe them some debt after waking them from their long slumber? As I said, this thinking is perhaps a one-way road, but nonetheless, there’s no doubt my efforts have rekindled some small slice of their existence.

I’ve recently seen AI (artificial intelligence) programs that will bring old images ‘back to life’ by creating new animations from a still photo (one such tool is called ‘Deep Nostalgia’). Apparently, it does not take a great deal of data for a neural network to infer or interpolate varying new facial angles, expressions, etc. Clearly, what is ‘taken’ in an original photograph can be used to recreate a sum far greater than its parts, so perhaps I am not so far off in feeling as I do about all these now dead people in Rubino’s images. If this reanimation technology is only in its infancy, there’s no telling where it could end up in rendering or creating actual revived versions of people (think ahead 75 years).

WHO CARES ANYWAY?

Aside from a few byline photos from his time as a photojournalist, there seems to be little info available about Aaron Rubino (at least online) - no articles, no obituary, no real context. My friend Tom added little, saying only that he was a ‘crazy’ old guy living in an unhappy marriage - they had never even discussed photography. It’s not that I felt so curious, but it seemed possible I was holding the last, large chunk of this guy’s work. If I pitched everything, were the last remains of his life going too? Because all these pieces of film were now in my hands, did they confer some hidden contract of responsibility, even though I never knew the man?

I can argue that some of Rubino’s photos are quite good, but a more objective or critical person might say most are mediocre at best. I would not necessarily argue with that assessment. There are plenty of mundane head shots, stereotypical wedding aisle snaps, and boring corporate PR images. Maybe it’s only some of the known names in the photos (Truman, Roosevelt, etc) or the historical venues pictured that lend some value to the images. And what about Rubino? Did he ever think he was shooting for posterity or creating art? I doubt it. I have a feeling it was mostly about the money for him, so again, why should I care where these end up?

There is some interest in ’vernacular’ or found images these days, but they seem to favor the oddities of humanity or the fringes of human culture. Many of those images revel in the exceptions, the anomalies, and the peculiar. For just the opposite reasons, some of Rubino’s images feel more human and compelling - people are viewed at their jobs or doing what they enjoy with the photographer trying to show them in the best possible light. Isn’t that basically what we do most of the time anyway? His photographs show a range of life as it was, perhaps mundane, even average, but not the edge cases or the extremes that often get attention. Certainly there is something worth preserving because of that alone. Beyond revealing some of the zeitgeist of the era, the images, viewed now, also reinforce that rather trite, but not insignificant, idea of how relative and transitory everything and everyone around us is.

Perhaps it’s only projection on my part, but I’ve always assumed most artists and photographers want their work to persist beyond their lives and somehow keep influencing the world from beyond the grave. Maybe Rubino understood something I have still failed to grasp - there is a time to let things go and perhaps that is what he did by giving them away. He knew the purpose behind the images and understood they had a short shelf-life. Still, I’m only guessing about his motivations and, in the end, feel an unease in making those final decisions for him, especially since some of his family pictures are intermingled. Perhaps it is something like unexpectedly ending up with a dead neighbor’s pet - you house it, feed it, and then either keep it or try to find it a good home. In the end, the images are not really ‘mine’ - I’m now just the caretaker and offer them up as such.

The Pictorial List thanks Gary for bringing this story to us, giving us an opportunity to see a glimpse into the life of a photographer during this eclectic era in history. We respectfully honor Aaron Rubino’s work and his contribution to photography in his day.

Gary has recently asked who may be interested in archiving these precious negatives of the past. They are a lovely depiction of life during a magical era in history in America, by a photographer that was committed to his work as a photojournalist, and freelance photographer documenting life as he saw it, through the lens.

If interested, please contact us via email and we will pass it on to Gary.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the text belong solely to the author/s, and are not necessarily shared by The Pictorial List and the team.