INTERVIEW

December 9, 2022

ZOONOSIS

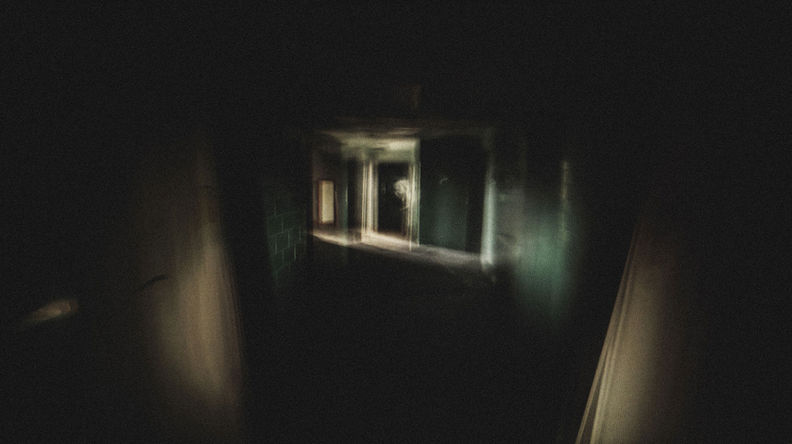

Photography by Adrian Pelegrin

Interview by Karen Ghostlaw Pomarico

Meet Adrian Pelegrin, a photographer originally from Barcelona, Spain, but currently living and working in Playa del Carmen, Mexico. He focuses his work, THE HYPERREAL ARCHIVE exploring and investigating the post-photographic edit and manipulation of images to create an awareness of fake news or an unreal reality. With the obsession of social media and its integration into our culture, Adrian studies the changes taking place in our society due to the cause of disinformation, and creates images reflecting the effects on society.

“My work is about mass media and how it creates new realities. I photograph archive videographic images, working mainly from television broadcasts. I make long-exposure photographic kinescopes that I later edit through digital post production.”

Adrian found the events of the pandemic and the biases of the media’s coverage along with their non objective point of view and transmitting of misinformation, to be the new focus for his exploration. His insightful study and research has culminated in his new book ZOONOSIS. Adrian shares with us how this book came to fruition.

“ZOONOSIS is a book gestated in pandemic times. When the global crisis broke out and the entire world was quarantined, I decided to start the task of documenting all the events that were coming to us through the media and online press. The book is the culmination of two years of tracking all the news about the novel coronavirus and its consequences, photographing television images, and selecting the most shocking headlines. Also, I have supplemented the visual and journalistic content with a concise historic-statistical investigation dedicated to synthesizing what happened as much as possible. At another level, I also contribute with a thesis, in a veiled way, juxtaposing different allegorical moments that the reader-observer will be able to guess when contemplating the book’s structure as a whole.”

Adrian is a photographer that thinks a great deal about the ideologies he wishes to expose, and draw our focus to. His photography confronts us with the new reality, making the viewer uncomfortable in the confrontation of truth. He has a deliberate vision and intent in how he approaches his work. This drives his process, and engages the viewer in a unique way. Adrian explains in detail his photographic process and critical and creative thought processes.

“Photography must express what words cannot express. Photography is a silent art that grows strong in silence. The photographer does not speak; the photographer only points out. Pointing out is to isolate and delimit the world. Photography is the fragmentary art par excellence. We do not see the world as it is, but as we are. A photograph that is defined beforehand is a dead photograph. A living photograph is one that is created and actualized by gaze.

Art records the seizures of the social. We must account for the events of our time. Photographing the archive, resampling its documents for a stab in the unconscious. Doing archeology of the present. Exploring the photographic dimension of movement, where overlays, sparkles, and unexpected analogies appear. Marginal elements emerge as untimely interferences, contiguities that generate metaphors: images of images in a double detachment from the real.

We are in the maelstrom of memory; in the hyperreal realm of simulacra. We see the phantasmagoria of a managed world, the dreams of instrumental reason. In the era of emptiness, mass disinformation becomes ubiquitous. Is this the real? Then, the artistic practice produces a paradox: the aesthetic paroxysm leads us to self-awareness.”

His insightful documentation and brilliant visual storytelling of the events of the pandemic brings us the harsh reality we are confronted with everyday, and how it allows for the distorted views of our future.

We have the fortunate pleasure of presenting Adrian’s interview, where he articulates in more detail about his extraordinary process in photography, and how it inspired this wonderful project and new book he has created, ZOONOSIS.

“We are in the maelstrom of memory; in the hyperreal realm of simulacra. We see the phantasmagoria of a managed world, the dreams of instrumental reason. In the era of emptiness, mass disinformation becomes ubiquitous. Is this the real? Then, the artistic practice produces a paradox: the aesthetic paroxysm leads us to self-awareness.”

IN CONVERSATION WITH ADRIAN PELEGRIN

THE PICTORIAL LIST: Hello Adrian, to begin, can you please tell us something about yourself. What would you say first drew you to photography?

ADRIAN PELEGRIN: I was born in Barcelona, Spain, in 1980. I grew up in Badalona, a post-industrial city by the sea. There was a combination of abandoned factories backing to the beach, fishermen, run-down suburbs, and an ancient Roman city steeped in history. Nearby is Barcelona, a large European city, where you can find all the fun you need as a young person and important cultural centers.

At the age of 15 (1995), I became interested in photography, thanks to a summer camp dedicated to film and print development. From then on, I never left the path; I installed my laboratory at home and worked intensely on it until the irruption of digital around the year 2000.

Today, I live in Playa del Carmen (Mexico), which is a long story, but to sum it up, I will say that I have been faithful to the belief that “we don’t have to die in the same place where we were born.” Besides that, I am focused on producing my most personal work (the Hyperreal Archive), mainly posting my progress on Instagram and materializing it in photobooks.

TPL: How would you describe your photography, and what would you say you are always trying to achieve artistically?

AP: I identify my work with the post-photographic trend that has become increasingly important in the last decade. The Internet and Social Media have had much to do with it, especially YouTube. The changes that have taken place are huge; today, the whole world lives through virtualized experiences, through the cell phone screen. That virtuality, what Baudrillard calls hyperreality, is like a parallel world. It replaces the sensitive life with the imagined life, the fantasized (in the Platonic sense of "phantasmagoria"). We live in a copy of a reality that is "degraded" (in another degree/level), although often, that degradation appears sublimated. All these historical-social phenomena are what interest me and what I try to talk about in my work. That is why I produce images of images; I never work with the "real" directly. Instead, I always start from previous materials, regurgitate them, and throw them back into that hyperreality in which everything is mixed up. We no longer know what is real and what is not.

TPL: Talk us through the narrative of ZOONOSIS. When and how did this project first manifest for you? What have you learned from this project that has surprised you?

AP: The book "Zoonosis" arose suddenly, just like the pandemic. In January 2020, I was working on another chapter of the "Hyperreal Archive" (that is the whole of my work's name); that chapter was "the Berlin wall." I was capturing images of the construction of the wall and the demolition. I was immersed in that historical-documentary inquiry process through Youtube materials. When the pandemic started, I didn't pay much attention to it. Still, as the months passed, I realized that it was a crucial historical moment, it was something too big, and I decided to stop everything to start documenting the pandemic. There is an important issue, and it has to do with censorship. In the beginning, many videos appeared (with which I worked), and after a few weeks, they disappeared. That's why it's crucial to document everything as it happens before the censors come with their scissors.

TPL: When telling a story about misinformation, using abstracted images, explain to our readers the importance of this vibrato of overlaid information, and why this technique became the vehicle to deliver your message.

AP: The idea came to me after reading Arthur Danto's book "After the end of art" I thought that the only thing left to do in art's history was to work from what was already done. More than producing, I do post-producing (for those interested in the subject, I highly recommend Nicolas Bourriaud's book "Post-production"). It's what DJs do; they remix the sampling. Taking samples from a formless mass of information and, from there, with that material, build a thesis. It is not new, but we live in the ideal historical moment to develop this movement. There is another book that also helped me, "Non-creative writing" by Kenneth Goldsmith (many poets hate it, by the way.) There is always reactionary resistance; the purists will tear their hair out at any innovation. Annoying the purists is something that has always appealed to me. In a world where all the information is pre-cooked and biased, it is naïve to claim purity, much less in art. It is something that Plato knew well; art does not reflect the truth but is a simulation.

TPL: Adrian, please tell our readers that are considering composing a photobook, what was your process? Where did you begin?

AP: There are two typical ways to plan a photo book or a book in general. One is to start from a preconceived idea, sketch each page and then photograph. Another is to start photographing and then try to find meaning in the material made. I am more in favor of the second option. Unless you have a clear idea of what you want to do and say, it's best to let things flow. You go in one direction, yes, within a topic, and you go on sifting and discarding what is left over. There comes the point where you start to see a meaning in it; interesting dissonances exist. Dissonances are unexpected moments (something that cannot be planned); they have to do with unconscious connections. That's why the anarchic method is the one that works best for me. Art has to differentiate itself from science and even adopt practices opposed to science. However, science has a lot to learn from art and vice versa. Planning and systematization castrate spontaneity and eliminate the possibility of psychoanalytic "dissonance"; those impurities, those "out of joint" moments, are indispensable.

TPL: Publishing a book is a long road to travel, with many unexpected turns and obstacles to overcome. Could you help our readers understand some of the pitfalls you have experienced, and give some wise advice on things you have learned, or perhaps would do differently next time around?

AP: Publishing a book on paper, nowadays, is absolute madness. It is the worst business you can imagine. In most cases, the editions are non-profit, even the authors end up putting money out of their pocket or giving the books away. That being said, some photographers do achieve their goals, not without strenuous work (which may never be financially rewarded). Publishing a book is a symbolic act, out of pure vanity or, at best, out of altruism. Different is creating a book, this process is essential, and every photographer should focus their efforts on producing books. The photobook format is on the rise, and there is no stopping it; it is part of the natural development of photographic art. We move from the "single photo" to the "photo essay." It is a significant epistemological leap. That doesn't mean that for most photographers selling books is a viable business. For those thinking of self-publishing, I recommend doing a crowdfunding campaign first (it doesn't cost any money), to test the market. Many times it happens that we overestimate the commitment of our followers. The reality is that our followers, and the majority of people who spend their time on social networks, are looking for free stuff. The fact that our photos receive a thousand organic likes on Instagram does not mean that you have an audience willing to take out their wallets. In any case, if you're still crazy enough to print your photo book on paper, I recommend doing some pre-work to gather subscribers and build an email list of potential buyers. From there, consider that only 5% of those subscribers are really willing to pay. When you are going to do a short print run, the book is so expensive that no one can afford it. The book is cheap if you do a long print run, but you need a solid fan base. You have to make numbers; and, in most cases, the numbers won't look good.

Annoying the purists is something that has always appealed to me. In a world where all the information is pre-cooked and biased, it is naïve to claim purity, much less in art. It is something that Plato knew well; art does not reflect the truth but is a simulation.

TPL: Since the pandemic is not over, will there be another edition to this book? If so, would you approach the misinformation in the media in a different way? Like Cause and effect, we understand the cause depicted and translated in this book, would there be a sequel to the effects the misinformation has had, and how as a society we have reacted?

AP: Today we can say that the pandemic is under control, and although the cases continue, a large part of the population is vaccinated. I think the worst is over because there is an essential genetic component in severe cases and deaths. Now there is the aftermath, the annoying constant colds, which we will have to learn to live with, and eventually, we will end up forgetting. More than a reworking or a continuation of the book, the important thing is to remember what has happened. The social, political, and economic context of 2020 is worth studying; it is a time we will return again and again. That is why it is worth making documentation covering all aspects of the epistemological spectrum, and the artistic expression has an important role.

As to whether we've learned anything from this trauma, I think it's too early to tell. Humans prefer to sweep the garbage under the rug instead of taking care of the problems. We always learn the hard way; when it's too late, and we don't take action until it all blows up.

TPL: Do you have any favourite artists or photographers you would like to share with us, and the reason for their significance?

AP: I am influenced by experimental photographers and artists such as Otto Steinert (subjectivity), Edward Steichen (pictorialism), Gerhard Richter (appropriation), and Joan Fontcuberta (post-photography), among many others. I am also interested in the critical theory of society and culture getting inspired by philosophers such as Theodor Adorno (aesthetics), Max Horkheimer (instrumentalism), Jean Baudrillard (hyperreality), and Jacques Derrida (deconstruction). Regarding paratactic writing, Tristan Tzara and William Burroughs (cut-up) have also been important references.

I am also very interested in the new generation of Japanese photographers; Japan will have an essential place in the world of photography in the coming decades.

TPL: How do you educate yourself to grow in your photography?

TPL: What was the first camera you ever held in your hand, brought to eye, and released a shutter on? What do you use now? Do you have your go to settings? Is there any equipment you have on your wishlist?

AP: Over the years, one learns that the camera is the least important. The photos are taken by the photographer, not by the camera. The gear is a tool. It's funny to see it this way. Do we ask a carpenter what brand of hammers he uses? Is this brand better than the other? And what brand of screwdriver? The important thing here is to have the tools; a hammer and screwdriver. The hammer brand is the least of it. If the hammer is of poor quality, it breaks, and you buy another one, that’s all. With photography, you have to think with the same parameters. There is an obsession about constant technological improvement, which doesn't make much sense.

That being said, my first camera was a Pentax MZ-50 (I think), and my last camera is a Canon 5Ds.

TPL: What comes next? What are some of your photography goals?

AP: As I suggested before, I have a much bigger and more ambitious project that consists of documenting the episodes of recent history through the information that comes to us from the Internet. I started with the Berlin Wall since it is my oldest memory, and I could experience it live on TV. Then came the war in the Persian Gulf, which was also somewhat shocking (in 1991, I was 11 years old). The idea is to continue the historical sequence. The pandemic was something that interrupted this work, but that also became part of the body of work. Now, I'm going to continue with the Hyperreal Archive, which is an infinite project and will last until I die. What I will be publishing will be different chapters of that broader project.

TPL: “When I am not photographing, I (like to)…

AP: I like to cover every one of my biological needs satisfactorily. After that, I like to read books (mainly philosophy), dedicate some time to entertainment, and watch films by Bergman, Fellini, Buñuel. Enjoy good music, Philip Glass, Charles Mingus. Traveling to nearby towns, going to the beach, eating lobster, watching football, drinking coffee…😁

The Pictorial List would like to thank Adrian for his insightful testimony to the events that took place during the course of the pandemic, and the role media played in influencing society and their reaction to the events that unfolded. Follow his work and watch him expose the realities as he dissects the disinformation, by confronting the truths, making obvious the manipulation and lies.